Is the Fed Secretly Ushering in the "New Economy"? Why Strong Growth Might Not Mean High Inflation

You know that classic economic dilemma: strong economic growth usually means things get hot, and prices—inflation—start climbing. So, why are we seeing prominent voices suggesting that the US can experience robust growth without triggering runaway inflation? Let’s dive into what was quietly discussed at the last FOMC meeting, because the key to this paradox lies in one powerful word: productivity. Here’s the thing, when productivity increases, you’re basically making more output for the same cost input . Think about a factory that used to make 10 items for $1,000; if automation and technology allow that same factory to now churn out 100 items for the same cost, the cost per item drops dramatically (from $100 to $10) . That efficiency means companies can sell goods for less while still making massive margins, leading to strong value creation and, crucially, lower inflation .

What’s interesting is that this isn't just theory; we’ve seen this movie before—it’s called “Again 1990” . During the 1990s, fueled by the rising IT bubble, then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan famously bucked the traditional thinking of his colleagues . While many central bankers argue for preemptive rate hikes when growth is high to curb future inflation, Greenspan said, "Hold on," arguing that rapid productivity gains, thanks to technology, were creating a “New Economy” where growth and low inflation could coexist . This counterintuitive insight—that a supply-side revolution (like technological leaps) can lead to lower prices even when demand is strong—is precisely the argument being echoed today .

This brings us directly to the current situation and the AI revolution. Analysts, including potentially future Fed Chairman Kevin Hassett, are suggesting that the massive capital expenditures by hyperscalers into AI infrastructure might be the 21st-century version of the 1990s IT boost . If these AI investments genuinely drive profound productivity improvements across the economy, we could potentially see strong growth stabilizing or even lowering inflation, rather than accelerating it . If this scenario plays out—strong growth and stable prices—it’s incredibly positive for asset markets, because you get robust economic activity without the central bank needing to slam the brakes on with high interest rates . This entire outlook is why the Fed’s latest projections included an increase in the growth forecast but a decrease in the inflation forecast—a seemingly impossible combination that the productivity revolution makes plausible .

Is the Fed Experiencing a Civil War, and How Does Trump Factor In?

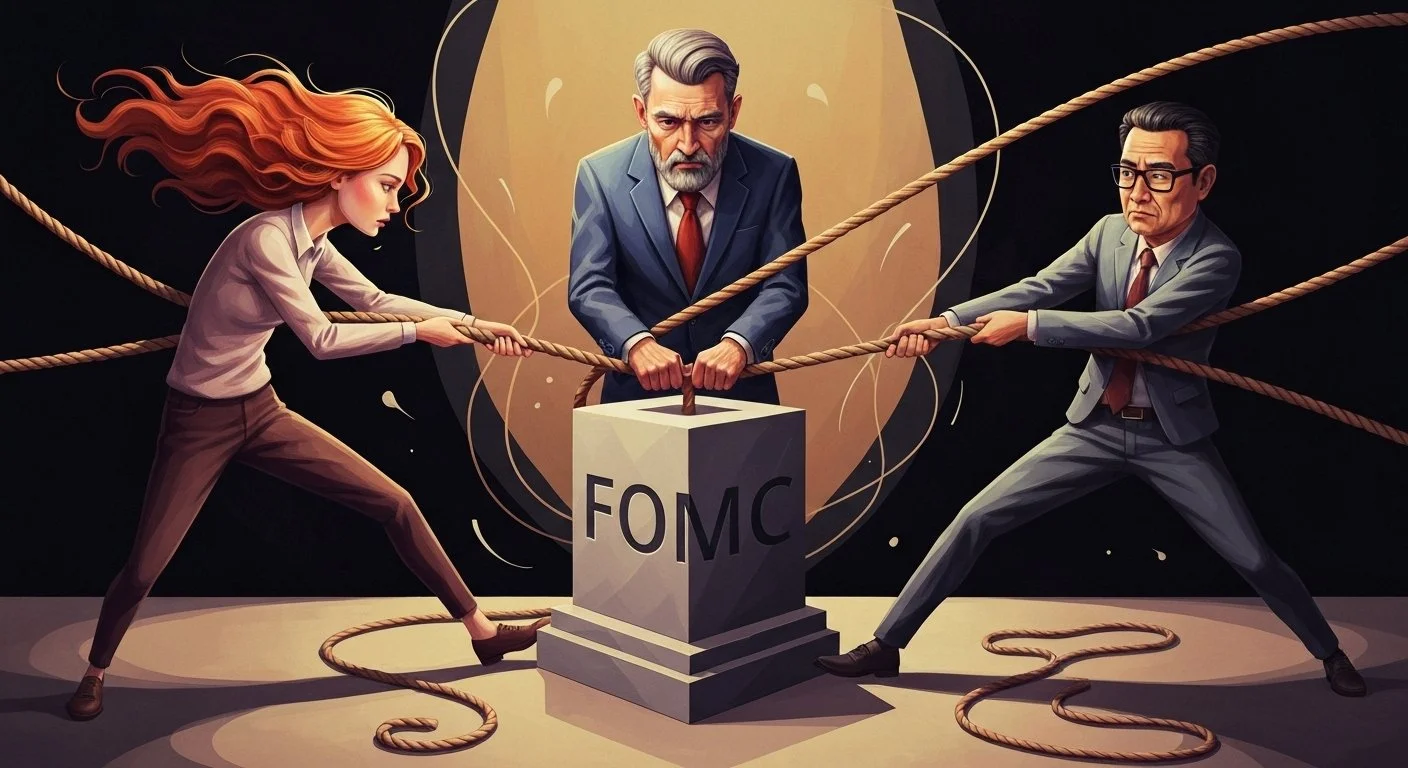

Here's the thing about the Federal Reserve: it’s not a monolith, and behind the closed doors of the FOMC, it often feels like a giant internal tug-of-war, or what some are calling a "Civil War" . You have members advocating for rate hikes, some for cuts, and others for maintaining the status quo, creating significant internal discord . Adding fuel to this fire are political elements, including concerns about Chairman Powell’s potential lame duck status and the influence of appointments favored by figures like former President Trump . When a central bank shows such deep division, markets naturally become nervous and highly reactive to any slight shift in rhetoric.

I've found that these internal splits become most obvious when the Fed has to deal with extraordinary or unconventional policies. For instance, the ongoing debate over the correct level of interest rates is complicated by external political pressures and shifting economic narratives, like the Trump administration's argument that current high inflation is merely a temporary issue related to tariffs, not classic economic overheating . If this view—that inflation is temporary and supply-shock-driven—takes hold, it gives the Fed more comfort in easing policy without fear of a wage-price spiral. However, the sheer volume of dissenting voices and the anticipation around future leadership appointments suggest that this institutional tension will remain a central theme for the foreseeable future, impacting how quickly and decisively the Fed can act.

This structural friction complicates the Fed’s messaging and execution, particularly concerning its unconventional monetary tools. The possibility of new appointees aligned with political figures like Trump—who often advocate for easier money—fuels market expectation and internal pushback from more traditional, data-dependent members . A key, often overlooked factor in this debate is the discussion around new leadership, which introduces massive uncertainty into policy continuity. Ultimately, whether it’s a “Civil War” or just spirited debate, this internal dynamic underscores the political and personal stakes involved in setting the world's most critical interest rate, making policy predictions far more complex than simply reading the latest jobs report.

Why is the Fed Buying Bonds if it's Not Quantitative Easing? The Mystery of the 'Soft Landing'

Lately, we’ve seen the Fed simultaneously talk about interest rate cuts and increasing government bond purchases, which sounds suspiciously like Quantitative Easing (QE)—the infamous money printing that floods the system with liquidity . But here’s the surprising fact: the Fed is explicitly denying that this is QE . Why the semantics? Traditional QE involves the central bank buying long-term government bonds, which pushes up bond prices, drives down long-term interest rates (like mortgage rates), and encourages investors to seek riskier assets, thus boosting asset prices across the board . This is a direct measure intended to stimulate the economy and inflate asset prices.

What’s happening now is different; the Fed is reportedly buying short-term Treasuries . They claim this action is not aimed at boosting asset prices but rather at managing the banking system’s operational liquidity, specifically the level of reserve balances held by banks at the central bank . Think of reserve balances as a bank’s cash cushion; having enough reserves is crucial to prevent a liquidity crisis, especially during stressful periods . From my experience analyzing past crises, the Fed's greatest fear is an unexpected "panic" moment in the short-term money markets, similar to what occurred in September 2019 .

This is where the fascinating analogy of the deep-sea diver comes in. Imagine the diver (the financial system’s reserves) going deeper and deeper during Quantitative Tightening (QT), where the Fed is pulling cash out . The Fed knows there is a point—a depth—where the diver will panic, but they don't know exactly where that point is . When they see early signs of panic in short-term markets (like in 2019 or recent mild stresses), they need to slow the tightening (tapering the QT) or even reverse slightly to restore liquidity to a "safe" or "optimal" level . The current bond buying is essentially this process of stabilizing the reserve balance, not a full-blown attempt to lower long-term borrowing costs or create a huge wealth effect . It’s less about a stimulus package and more about internal plumbing—a technical adjustment to prevent the system from going "ungh!" and crashing, akin to zeroing a rifle in the military . While this isn't the massive, indiscriminate QE that makes markets go wild, it's definitely a beneficial form of easing, suggesting the Fed is carefully maneuvering to maintain stability while finding that Goldilocks zone of reserve liquidity .