The Currency Collapse: Why Is Iran’s Economy Reaching a Tipping Point?

When we look at major global upheavals, we often think of political unrest or military conflict, but sometimes, the real fuse is lit by something as seemingly mundane as the exchange rate. Here’s the thing about Iran right now: the economic situation, especially the "crazy exchange rate," isn't just about inflation; it’s a direct threat to the very structure of the government, and it’s fueling massive, surprising protests. What's truly interesting is that while the Iranian government's mismanagement certainly plays a part, the core of the crisis stems largely from external sanctions, meaning they have tons of money—they just can't use it. This volatile mix of external pressure and internal corruption has created a currency crisis so extreme that it's challenging the status quo in ways we haven't seen in decades.

Why Can’t Iran Stop the Currency from Tanking?

Have you ever tried to manage a national budget when most of your money is frozen? That’s the impossible position Iran finds itself in, and it's why they can't effectively defend their currency . Despite having an estimated $120 billion in foreign reserves, the government can only actually access and spend about 25% of that wealth due to international sanctions . Imagine having $100 in the bank but only being able to use $25 to pay your rent and buy groceries—it makes controlling the market nearly impossible! This reality means that when the dollar value surges, the central bank’s usual interventions are seriously limited, creating a runaway train scenario for the free market exchange rate.

This inability to stabilize the currency has had dramatic consequences, and the numbers are absolutely staggering. Back in the Obama era, when the nuclear deal was first solidified, the free market exchange rate hovered around 32,000 rials per dollar; when Trump first took office, it jumped to 50,000, which was concerning enough. However, by 2022, we saw it hit a shocking 450,000 to 500,000 rials, and recently, during the latest protests, the value plunged further, reaching between 1,300,000 and 1,400,000 rials per dollar . I've found that this kind of hyper-devaluation doesn't just erode savings; it fundamentally destroys trust in the financial system and the government’s ability to function.

This leads us to a highly counterintuitive insight: the government's attempt to manage this crisis actually fueled corruption that made the situation worse. To try and stabilize prices for essential goods like food and medicine, the government created a multi-tiered currency exchange system, offering the cheapest subsidized dollars (about 42,500 rials per dollar) to importers of necessary commodities. However, this system became a goldmine for powerful, connected merchants: they would claim millions of dollars at the subsidized rate to import essentials, only purchase a small fraction of goods, and then sell the remaining cheap dollars at the much higher free market rate for enormous, illicit profits . It's a shocking cycle where economic policy designed to help the common people was hijacked by the elite, confirming the public's worst fears about systemic rot and contributing directly to the skyrocketing prices.

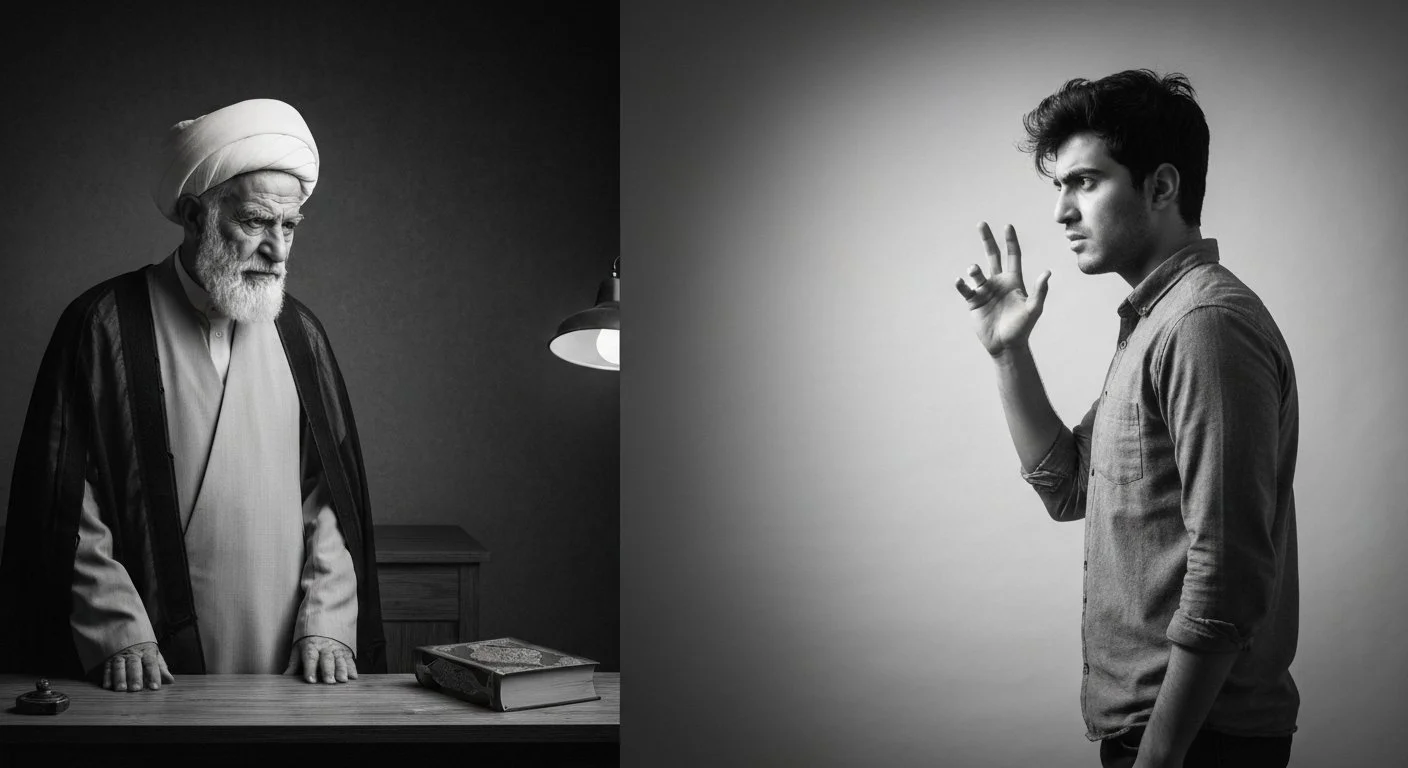

Who is Angrier: The Students or the Merchants?

We often see images of students and young activists protesting, but the truly surprising and dangerous shift in Iran's recent unrest is the involvement of the merchant class . In late 2022, it was the market merchants—the Bazaar—who shut down their shops in protest because of the hyperinflation, sparking widespread alarm within the regime . This is a crucial historical connection, as the support of the merchants was instrumental in the success of the 1979 Iranian Revolution; simply put, without the backing of the Bazaar, the regime cannot change, and it certainly cannot survive . From my experience analyzing protest movements, when the people who keep the economy running join the streets, it signals a fundamentally different—and deeper—level of dissatisfaction than just student activism.

The speed of the price increases was so rapid that merchants simply couldn't sell goods, fearing they wouldn't be able to replace their inventory at the constantly climbing free-market exchange rate. Imagine going to bed and waking up to find your inventory is 50% more expensive to replace than it was yesterday; how can you price anything fairly? For example, when the exchange rate was around 600,000 rials per dollar, a simple order of two coffees, one tea, and two slices of cheesecake at a nice hotel (the equivalent of about $25 in a Western five-star hotel) cost the equivalent of a few thousand rials in local currency. But if the currency value drops by half, the real cost of those foreign goods doubles overnight, crushing consumer purchasing power, making life unbearably expensive for the average citizen, and sparking outrage over the huge income-salary mismatch .

The government, realizing the existential threat posed by the merchant strikes, quickly changed tactics from confrontation to negotiation. Unlike student protests, which can often be dispersed, the merchants have established guilds and leadership, making direct talks possible—a surprising advantage for the government in a crisis. Their "solution" was to completely scrap the multi-tiered, subsidized exchange rate system and move everything to the market rate, eliminating the corruption incentive, while offering a meager temporary stipend of 10 million rials (about $7 at the current market rate) to citizens for four months . Yet, experts agree this is just a temporary bandage, or a "lame solution," because without addressing the root cause—the sanctions and the corruption—inflation is guaranteed to soar again.

What is Fueling the Younger Generation's Discontent?

The current unrest isn't just financial; it’s driven by a massive generational gap and deep social resentment, particularly among Iran’s youth, known as the 'Z-generation'. It’s a strikingly young country, with around 50% of the population under the age of 30, but the current political and religious leadership is exceptionally old, often born in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s . These aging leaders struggle to understand a generation that, for instance, often refuses to wear the obligatory headscarf (hijab) and, surprisingly, the government often chooses to ignore this defiance rather than enforce the rules, realizing that suppression might create even greater unrest . This tacit acceptance of disobedience highlights the government's vulnerability and its deep discomfort with a vocal, uncompromising youth demographic.

This generation also harbors strong feelings of historical betrayal, with many young people reportedly asking their parents, "Why did you make the revolution?". They were promised a utopian future after 1979, but instead, they inherited an economy in decline, especially after the devastating eight-year Iran-Iraq war and persistent international isolation. What’s truly infuriating the public now is the perceived misuse of national wealth, especially the billions earned during the early 2000’s oil boom, which opponents argue was spent funding anti-Israel proxy forces abroad and supporting religious institutions, rather than investing in domestic economic development.

The outrage peaked when the government revealed a budget proposal that increased funding for these non-essential sectors while only offering a 20% wage hike against an inflation rate of 50%, essentially ensuring that citizens got poorer. Protesters are not demanding that the government miraculously create money; they are simply demanding that the existing, finite resources be spent for them—the Iranian citizens—and not for foreign causes like Gaza or Lebanon . In a nutshell, the economic crisis is fundamentally tied to a moral one: the money is being spent on the wrong priorities, and that is what the young, bold generation is finally demanding to change.